Beveridge was named after Scottish sheep farmer Andrew Beveridge who built the Hunters' Tryste Inn in 1845. The Inn still serves as a

hotel, as well as post office and general store. Beveridge Post Office opened on 1 January 1865. Near Beveridge is Mt Fraser, from this

location the explorers Hume and Hovell first saw Port Phillip Bay on 14 December 1824.

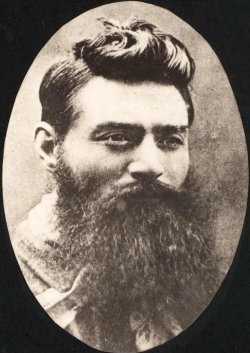

The town is principally known as the birthplace of bush ranger Ned Kelly and his home for the first nine years of his life. Ned's birth was

not officially recorded. At Beveridge a cottage where the Kelly family lived for a short time is still standing today, located on Kelly Street.

It is recorded that John Kelly built this house in 1859 when Ned was about five years old. His brother Dan was born in the house. The

house was added to the Victorian Register of Historic Buildings in September, 1992. Its design is unusual in Victoria and shows the Irish

heritage of its builder.

The Railway station opened on October 14, 1872. A goods shed was provided on opening, until moved in 1885 to the down side of the

line. The final station building was located on the down platform and was transferred from Bright to replace the original in October 1900.

The platform of the station was extended in 1883, with duplication of the line from Donnybrook and construction of the Melbourne bound

platform carried out the same year. Duplication continued northwards in 1886. The station was closed on April 2, 1990 and the platforms

were removed on February 14, 1991. Today the platform mounds can still be seen, as well as the slewing of the parallel standard gauge

line away from the former up platform, and the widening of the railway reserve.

Ned Kelly was born at Beveridge, Victoria, in December 1854, the same year as the Eureka Stockade uprising in Ballarat, and was the

eldest of eight children. So he arrived amidst a climate of political unrest and outright revolution - no wonder he turned out the way he did.

As a boy he attended school and risked his life to save another boy who was drowning. As a reward he was given a sash, which he

would wear under his armour during his final showdown with police. Kelly was a "bush-worker" in his teens, breaking in horses,

mustering cattle and maintaining fences - but graduated from that to cattle-rustling and horse - stealing. Over sixty thousand Victorians

signed a petition against Kelly's later sentencing, and an inquiry was held in which all the police officers involved in Ned's exploits were

either made redundant or demoted.

Today, in the eyes of many, Ned Kelly has become Australia's foremost folk–hero and a symbol of national pride. Certainly, Ned

possessed qualities that far surpassed the other bush rangers of his era. He was an expert with a “running-iron” on stolen, unbranded

stock and was a deadly–accurate shot with a revolver or a rifle. Despite being a largely self–educated man, he was surprisingly articulate,

boasted an almost poetic turn of phrase and a sardonic sense of humour. Ned’s family meant everything to him and he was the man of the

family at the age of twelve. He was fiercely Loyal to his friends and supporters, to the extent that he would risk his own skin to ensure the

well-being of an ally. To the last, his mocking courage never deserted him and to be “as game as Ned Kelly”; came to symbolise, in

Australian folk-language, heroism of a reckless, audacious kind.

It was inevitable that Ned, the eldest of the Kelly boys, should become a resourceful bush-worker while still in his teens. He did many things

to earn a few shillings for the family, such as ring-barking, breaking in horses, mustering cattle, fencing and perhaps a little cattle-duffing

on the side. Many of the settlers in the area were small selectors who were at constant war with the big landowners (the squatters) who,

at any time, could call on the forces of law and order to protect their interests. In this social war can be found the key to Ned Kelly’s rebellion

against authority. The Kelly boys, the Quinns, the Lloyds and the rest used horses like currency. They regarded all unbranded strays as fair

game and the police patrols as their natural enemies. The police in Kelly Country also bitterly resented the clannishness of the small selectors

and were determined to break them. When Superintendent Nicholson, a Scot, took over the north-eastern police district, he was told that Mrs

Kelly's house was a notorious meeting place for rogues and cattle-thieves. He gave Mrs Kelly a stern warning, to which she responded

with a spirited retort.

In 1874 police, unable to find another horse-thief, swore warrants against both Ned and Dan Kelly. The trooper who came with the warrant

was a weak willed man named Alexander Fitzpatrick, who had called at a tavern on his way to Mrs Kelly's place to fortify his intent. About

five minutes after the lone trooper entered the homestead violence erupted. Fitzpatrick made a drunken pass at Kate Kelly. Dan knocked him

down and, in the ensuing scuffle, the trooper's gun went off and he cut his wrist, most likely on the door-latch. Mrs Kelly was full of concern.

She bandaged his wrist and he was invited to have supper with the family and “let bygones be bygones”. On his way back to police barracks,

Fitzpatrick had some more brandy.

He then reported to his superiors that Dan Kelly had resisted arrest, and that Ned had burst into the room and shot him in the wrist. Ned then

offered to cut out the bullet with a rusty razor blade but Fitzpatrick decline, opting to use his penknife to dig it out. In spite of Mrs Kelly’s

protests that Ned was 400 miles away and, anyway, nobody had shot Fitzpatrick, arrests were made. Mrs Kelly was sentenced to three

years in gaol. Fitzpatrick was discharged ignominiously from the police force for misconduct in another case. But by then the damage had

been done. Ned Kelly swore vengeance. Restrained by his friends, he instead wrote an impassioned letter to Magistrate Wyatt, offering to

surrender his own person “to any charge” in exchange for his mother, but Wyatt was powerless to act. By then the police were increasing

their efforts to get Ned Kelly.

Much is made of the history of Ned Kelly and many would paint him as an Australian folk heroe, but police constables of the district would

tell a very different story in October 1878. Sergeant Kennedy, with Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and McIntyre, rode out from Mansfield to

hunt the Kelly gang. Making one of his regular reconnoitres, Kelly spotted the police camp and hurried back to raise the alarm. The next day,

Kennedy and Scanlon rode out on patrol, leaving only Lonigan and McIntyre in camp. The two troopers were relaxing by the campfire when

Ned, Joe, Steve and Dan emerged silently from the bush. They challenged the troopers and ordered them to bail.

Lonigan jumped to his feet and drew his revolver but Ned shot him dead. McIntyre surrendered immediately. When Kennedy and Scanlon

returned to the camp Ned killed Kennedy while Joe Byrne finished off Scanlon but McIntyre managed to escape on Kennedy's horse.

Constable McIntyre reached Mansfield to raise the alarm and repeated the story of a cowardly ambush by the Kelly's and a mass slaughter,

which shocked Mansfield and, in time, the whole country. Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne were proclaimed outlaws, to be

taken dead or alive. Controversy arose in 2007 when it was suggested that Ned Kelly be used as an emblem for the Victorian armed crimes

task force, the idea was quickly abandoned!

Edward 'Ned' Kelly was born at Beveridge in 1855, the first-born son of an Irish Catholic couple. His father, John 'Red' Kelly was an

ex-convict (transported for the theft of two pigs), who eloped with Ellen Quinn, an Irish 'bounty migrant', from Van Dieman's Land (later

Tasmania) to Port Phillip. The Kelly's settled in the Victorian ranges north of Melbourne, eking out a living on the edge of the squatter's rich

ands. Red Kelly supplemented his income by horse stealing. After his arrest and gaoling for horse-stealing, Red Kelly died before finishing

his sentence. Ellen moved the family to a slab hut at Eleven Mile Creek in the north-west of the colony where Ned became the main bread

winner, taking jobs as a timber cutter and rural worker - ringbarking, breaking in horses, mustering cattle and fencing.

Ned Kelly grew up with the tales of bush rangers and knew the tale of Ben Hall well. At the age of 14, Ned was arrested for stealing 10

shillings from a Chinese man and reportedly to have announced that he was “going to be a bush ranger”. Ned was sent as a kind of

apprentice bush worker to Harry Power, one of the last of the convicts transported to Van Dieman's Land in 1842 for stealing a pair of shoes,

who took to bush ranging after escaping from Pentridge Gaol. A year later, Kelly was charged with robbery under arms on one occasion

when he was holding Power's horse. He was freed for lack of evidence, although a few months later has was back in the lockup for

assault. During this time, Ned also gained some notoriety as the champion boxer in the Beechworth district. Bush ranging was said to have

ended with the shooting of the Kelly Gang in 1880 at Glenrowan, Victoria, made possible by the introduction of the Felons Apprehension Act

1865 (NSW) which allowed outlawed bush rangers to be shot, rather than arrested and sent to trial.

Private Frederick Arthur Foster, 17 Bn, 5th Brigade, 2nd Division AIF, who was killed in action at First Bullecourt on 15 April 1917, was a

nephew of Ned Kelly. His mother, Kate Foster nee Kelly, was a younger sister of the famous outlaw. On 23 June 1916, Foster embarked at

Sydney in HMAS Barambah which reached Plymouth on 25 August 1916. After training in England, he embarked on 28 February 1917 at

Folkestone in SS Golden Eagle for France. The 5th Brigade, including the 17th Battalion, on 13 April 1917 relieved the hard pressed 13 Brigade

of the 4th Division. The 17th Battalion was located south of Bullecourt at Noreuil and Lagnicourt. On the morning of 15 April, 26 German

battalions, the greater part of 4 divisions, without preliminary bombardment, as a surprise measure, attacked the positions of the 1st and 2nd

divisions at Lagnicourt. The Australians fought desperately and repulsed the attack. It was in this action that Frederick Foster was killed. It is

reputed that Frederick Foster's last words to the Anglican padre who bent over him were: `Kiss me Granny.' He had lived with Ellen and Jim

Kelly since he was 9 years of age. Foster's records state that he is buried in the vicinity of Lagnicourt but his grave is not marked. His name

appears on the Villers Bretonneux Memorial where the names of over 11,000 Australians who died in France and have no known grave are

recorded.

One of the first to take advantage of the Robert Mason survey of the now Beveridge township in 1852 and sale of the township allotments

was John Kelly father of Bush ranger Ned Kelly. Transported from Ireland in 1841, he served his two years in imprisonment in Van Diemens

Land and worked on a farm until 1848 when he was freed. He was by this time twenty-nine, could read, but not write, and had some skill

as a carpenter. Finding his way to this new township, he fell in love with Ellen Quinn, and despite parental ban, they rode to Melbourne to

marry at St. Francis Church on 18th November, 1850. The small home John built for his bride still stands as part of the larger additions we see

today.

hotel, as well as post office and general store. Beveridge Post Office opened on 1 January 1865. Near Beveridge is Mt Fraser, from this

location the explorers Hume and Hovell first saw Port Phillip Bay on 14 December 1824.

The town is principally known as the birthplace of bush ranger Ned Kelly and his home for the first nine years of his life. Ned's birth was

not officially recorded. At Beveridge a cottage where the Kelly family lived for a short time is still standing today, located on Kelly Street.

It is recorded that John Kelly built this house in 1859 when Ned was about five years old. His brother Dan was born in the house. The

house was added to the Victorian Register of Historic Buildings in September, 1992. Its design is unusual in Victoria and shows the Irish

heritage of its builder.

The Railway station opened on October 14, 1872. A goods shed was provided on opening, until moved in 1885 to the down side of the

line. The final station building was located on the down platform and was transferred from Bright to replace the original in October 1900.

The platform of the station was extended in 1883, with duplication of the line from Donnybrook and construction of the Melbourne bound

platform carried out the same year. Duplication continued northwards in 1886. The station was closed on April 2, 1990 and the platforms

were removed on February 14, 1991. Today the platform mounds can still be seen, as well as the slewing of the parallel standard gauge

line away from the former up platform, and the widening of the railway reserve.

Ned Kelly was born at Beveridge, Victoria, in December 1854, the same year as the Eureka Stockade uprising in Ballarat, and was the

eldest of eight children. So he arrived amidst a climate of political unrest and outright revolution -

would wear under his armour during his final showdown with police. Kelly was a "bush-

either made redundant or demoted.

Today, in the eyes of many, Ned Kelly has become Australia's foremost folk–hero and a symbol of national pride. Certainly, Ned

possessed qualities that far surpassed the other bush rangers of his era. He was an expert with a “running-

boasted an almost poetic turn of phrase and a sardonic sense of humour. Ned’s family meant everything to him and he was the man of the

family at the age of twelve. He was fiercely Loyal to his friends and supporters, to the extent that he would risk his own skin to ensure the

well-

It was inevitable that Ned, the eldest of the Kelly boys, should become a resourceful bush-

at any time, could call on the forces of law and order to protect their interests. In this social war can be found the key to Ned Kelly’s rebellion

against authority. The Kelly boys, the Quinns, the Lloyds and the rest used horses like currency. They regarded all unbranded strays as fair

game and the police patrols as their natural enemies. The police in Kelly Country also bitterly resented the clannishness of the small selectors

and were determined to break them. When Superintendent Nicholson, a Scot, took over the north-

In 1874 police, unable to find another horse-

five minutes after the lone trooper entered the homestead violence erupted. Fitzpatrick made a drunken pass at Kate Kelly. Dan knocked him

down and, in the ensuing scuffle, the trooper's gun went off and he cut his wrist, most likely on the door-

Fitzpatrick had some more brandy.

He then reported to his superiors that Dan Kelly had resisted arrest, and that Ned had burst into the room and shot him in the wrist. Ned then

offered to cut out the bullet with a rusty razor blade but Fitzpatrick decline, opting to use his penknife to dig it out. In spite of Mrs Kelly’s

protests that Ned was 400 miles away and, anyway, nobody had shot Fitzpatrick, arrests were made. Mrs Kelly was sentenced to three

years in gaol. Fitzpatrick was discharged ignominiously from the police force for misconduct in another case. But by then the damage had

been done. Ned Kelly swore vengeance. Restrained by his friends, he instead wrote an impassioned letter to Magistrate Wyatt, offering to

surrender his own person “to any charge” in exchange for his mother, but Wyatt was powerless to act. By then the police were increasing

their efforts to get Ned Kelly.

Much is made of the history of Ned Kelly and many would paint him as an Australian folk heroe, but police constables of the district would

tell a very different story in October 1878. Sergeant Kennedy, with Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and McIntyre, rode out from Mansfield to

hunt the Kelly gang. Making one of his regular reconnoitres, Kelly spotted the police camp and hurried back to raise the alarm. The next day,

Kennedy and Scanlon rode out on patrol, leaving only Lonigan and McIntyre in camp. The two troopers were relaxing by the campfire when

Ned, Joe, Steve and Dan emerged silently from the bush. They challenged the troopers and ordered them to bail.

Lonigan jumped to his feet and drew his revolver but Ned shot him dead. McIntyre surrendered immediately. When Kennedy and Scanlon

returned to the camp Ned killed Kennedy while Joe Byrne finished off Scanlon but McIntyre managed to escape on Kennedy's horse.

Constable McIntyre reached Mansfield to raise the alarm and repeated the story of a cowardly ambush by the Kelly's and a mass slaughter,

which shocked Mansfield and, in time, the whole country. Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne were proclaimed outlaws, to be

taken dead or alive. Controversy arose in 2007 when it was suggested that Ned Kelly be used as an emblem for the Victorian armed crimes

task force, the idea was quickly abandoned!

Edward 'Ned' Kelly was born at Beveridge in 1855, the first-

ands. Red Kelly supplemented his income by horse stealing. After his arrest and gaoling for horse-

Ned Kelly grew up with the tales of bush rangers and knew the tale of Ben Hall well. At the age of 14, Ned was arrested for stealing 10

shillings from a Chinese man and reportedly to have announced that he was “going to be a bush ranger”. Ned was sent as a kind of

apprentice bush worker to Harry Power, one of the last of the convicts transported to Van Dieman's Land in 1842 for stealing a pair of shoes,

who took to bush ranging after escaping from Pentridge Gaol. A year later, Kelly was charged with robbery under arms on one occasion

when he was holding Power's horse. He was freed for lack of evidence, although a few months later has was back in the lockup for

assault. During this time, Ned also gained some notoriety as the champion boxer in the Beechworth district. Bush ranging was said to have

ended with the shooting of the Kelly Gang in 1880 at Glenrowan, Victoria, made possible by the introduction of the Felons Apprehension Act

1865 (NSW) which allowed outlawed bush rangers to be shot, rather than arrested and sent to trial.

Private Frederick Arthur Foster, 17 Bn, 5th Brigade, 2nd Division AIF, who was killed in action at First Bullecourt on 15 April 1917, was a

nephew of Ned Kelly. His mother, Kate Foster nee Kelly, was a younger sister of the famous outlaw. On 23 June 1916, Foster embarked at

Sydney in HMAS Barambah which reached Plymouth on 25 August 1916. After training in England, he embarked on 28 February 1917 at

Folkestone in SS Golden Eagle for France. The 5th Brigade, including the 17th Battalion, on 13 April 1917 relieved the hard pressed 13 Brigade

of the 4th Division. The 17th Battalion was located south of Bullecourt at Noreuil and Lagnicourt. On the morning of 15 April, 26 German

battalions, the greater part of 4 divisions, without preliminary bombardment, as a surprise measure, attacked the positions of the 1st and 2nd

divisions at Lagnicourt. The Australians fought desperately and repulsed the attack. It was in this action that Frederick Foster was killed. It is

reputed that Frederick Foster's last words to the Anglican padre who bent over him were: `Kiss me Granny.' He had lived with Ellen and Jim

Kelly since he was 9 years of age. Foster's records state that he is buried in the vicinity of Lagnicourt but his grave is not marked. His name

appears on the Villers Bretonneux Memorial where the names of over 11,000 Australians who died in France and have no known grave are

recorded.

One of the first to take advantage of the Robert Mason survey of the now Beveridge township in 1852 and sale of the township allotments

was John Kelly father of Bush ranger Ned Kelly. Transported from Ireland in 1841, he served his two years in imprisonment in Van Diemens

Land and worked on a farm until 1848 when he was freed. He was by this time twenty-

marry at St. Francis Church on 18th November, 1850. The small home John built for his bride still stands as part of the larger additions we see

today.

Get all the news at TalkNews.com.au

Non Stop Music

National Live Shows

admin [@] nedkellyfm.com